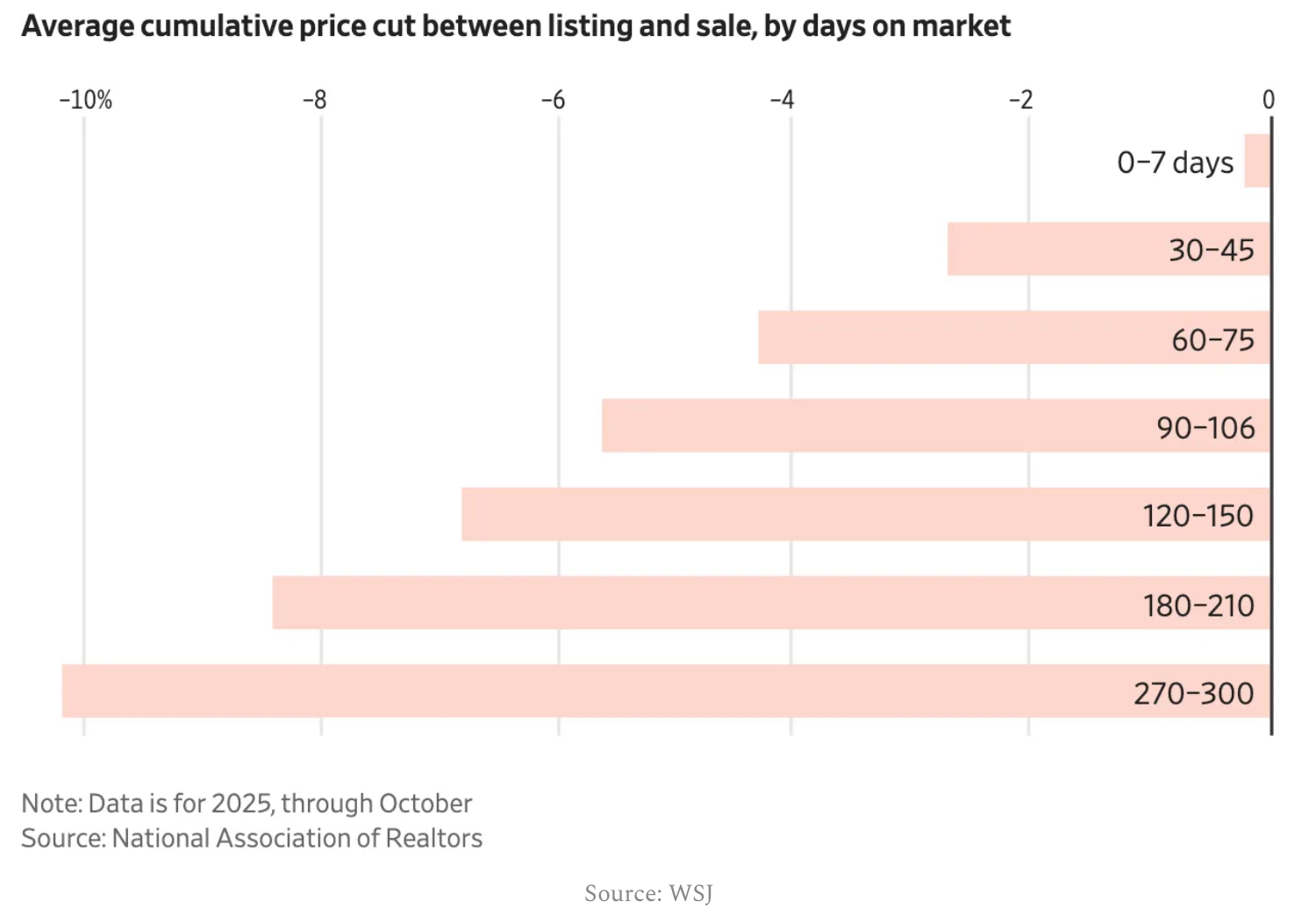

In 2025 through October, about 57% of U.S. home sales had at least one price cut, and properties that needed cuts typically took far longer to sell than accurately priced listings from the start. The more overpriced a listing is, the greater the number of incremental cuts it usually requires, which extends days on market and increases the eventual discount from the final asking price, with homes selling within 30 days generally achieving at or above their last list price.

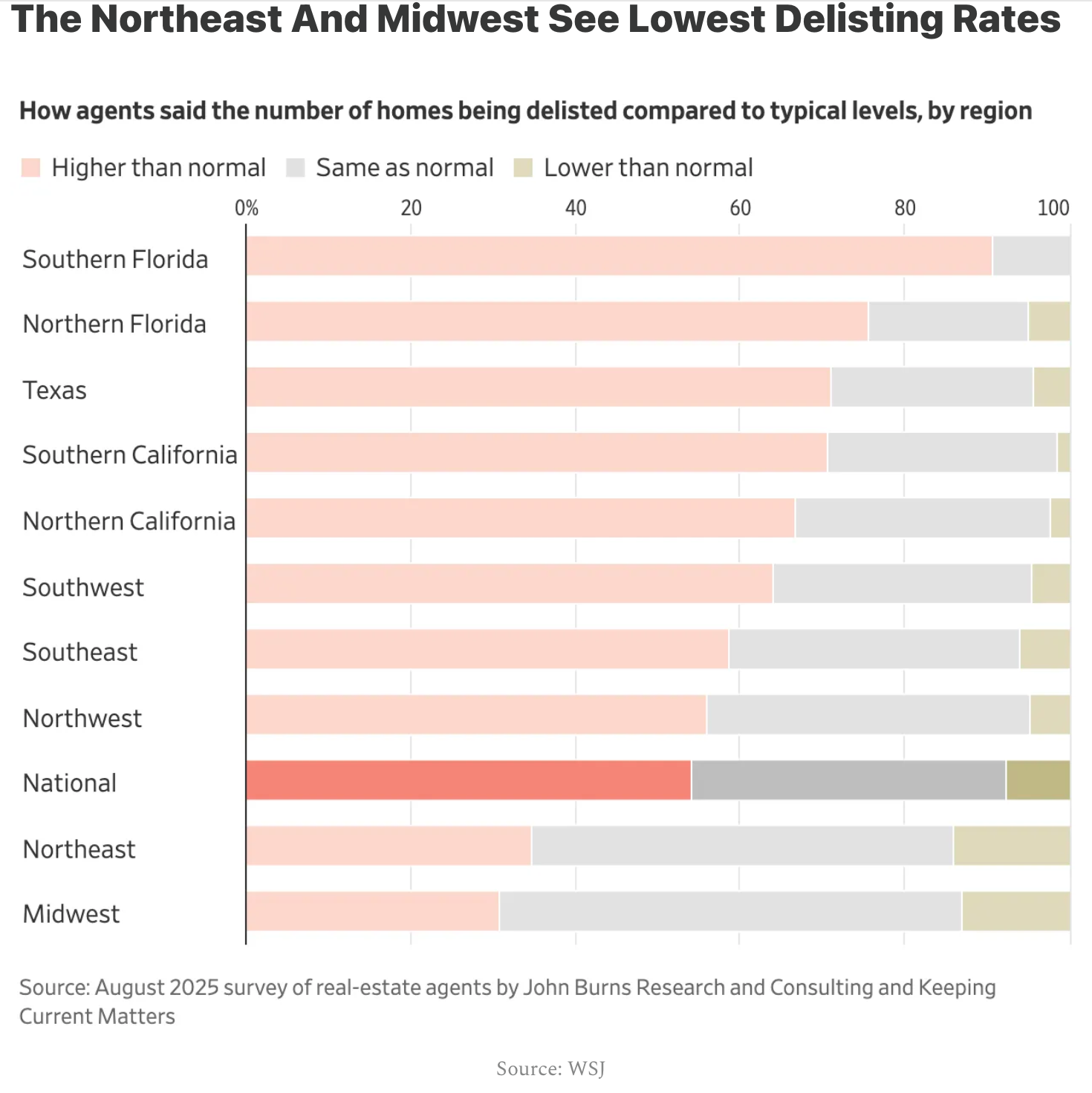

Delistings remain lowest in the Northeast and Midwest, where tighter inventory supports demand, while a parallel push toward private or off‑MLS “test” listings delivers little proven pricing premiums, sells a small share privately and often lengthens time to sell despite industry claims.

More than half of all listings had a price cut in 2025

There was a great Wall Street Journal article a few weeks ago, “When Home Sellers Set Prices Too High, They’re Paying for It,” that I’ve been itching to write about. Sellers had a good run with limited competition until the past year, so many still crave the freedom to “test the market.” What that really means to most sellers is to set a listing price they know is too high for the current market.

I remember giving a keynote presentation to real estate agents in a suburban market a while back. An agent asked me a question during the Q&A (and this was the actual question I recalled from memory): “What if a Middle Eastern oil sheik makes a high offer for my house? Shouldn’t I price it high to get one of those offers?” Kiddingly, I asked the agent if she had asked the seller if they were familiar with the internet and if the seller thought that the fabulously wealthy potential buyer looking at the seller’s raised-ranch four-bedroom, two-bath with aluminum siding and a faux brick facade in a generic suburban location, with an above-ground pool and an old roof, had access to the internet, too?

About 20 years ago, my New York University colleagues and I authored a white paper titled “The Condominium v. Cooperative Puzzle: An Empirical Analysis of Housing in New York City.” But the band broke up as my colleagues pursued opportunities at new institutions, and the next project was never finished. Our next project was to measure the value of the damage caused by overpricing a listing.

A listing carries reputational risk in the market through its pricing, the listing agent’s track record and the seller. A significantly overpriced listing may reflect badly on a listing agent, but only if all their listings are significantly overpriced. All those listings probably wouldn’t all have had a very unreasonable seller. After a trial run at a high price, reducing the price to market levels probably still carries the baggage of its initial disconnect from the market. There can be difficult sellers, or there can be listing agents who will take any listing, no matter how unrealistically high the seller demands the price to be.

The WSJ article illustrated what most real estate agents already know: the more overpriced a listing is, the more price cuts it requires. One of the biggest challenges for an agent is dealing with an unrealistic seller. The sellers tend to “catch a falling knife” and rarely make a large enough price cut soon enough to meet the market. More price cuts tend to lead to longer marketing times.

Source: The Wall Street Journal via HousingNotes.

Source: Miller Samuel/Douglas Elliman via HousingNotes.

Internally, we analyze days on market and listing discount patterns in the market reports we produce. The WSJ article that used NAR data relied on the number of price cuts. We do something similar, but on a more limited scope. I grabbed data showing the relationship between the sale price and the last listing price. Generally speaking, listings with higher market share and faster sales correlated with smaller discounts. In fact, in all three markets, anything that sold within 30 days sold at a premium (and negative listing discount). In other words, the listings sold for more than the asking price at the time of sale.

Shorter marketing time equals lower discount equals closer proximity to market value.

Source: The Wall Street Journal via HousingNotes.

Listings that never sell are referred to as “delisted” when they are removed from the market. Both the Midwest and the Northeast continue to see the lowest delisting rates because they don’t have the excess listing inventory seen in other parts of the U.S.

Private listings for ‘testing’?

One of the biggest reasons given to justify private listings is to enable the seller to “test the market.” What that really means is for the seller to see if they can get a “dream” price detached from reality. In fairness, some unique properties are very hard to price. I get it; I’m an appraiser. Compass reports that 94% of its listings that begin as private or premarket eventually go public on the MLS. So, let’s be honest. I believe that means only 6% of private listings sell as private listings. Therefore, this isn’t really a mechanism to test the price, since it isn’t exposed to nearly as many “eyeballs” as a public listing, as evidenced by their 94% figure internally.

In a Bright MLS research piece, “On-MLS Study,” often incorrectly cited by the industry, there was a 17.5% premium for public listings over private listings. The reason for the premium was that non-MLS listings, which include FSBOs, tend to be significantly lower in price, thereby skewing the mix. After removing FSBOs, there doesn’t seem to be a price difference between public and private listings, which is counter to my own experience. But as I like to say, anecdotal is not data.

Mike DelPrete has a great piece on this, “Logical Fallacies, Seller Motives, and Private Exclusives.” After removing FSBOs (a legitimate part of the sales market) from non-MLS listings, the premium for public over private seems to vanish based on the nominal differences tracked by Compass, NAR, Zillow and Bright. So, this begs the question: Why is Compass, the largest U.S. real estate brokerage company by far (and getting much bigger in 2026), making private listings their core marketing strategy, transparent to just their own agents, when only a small share of the market actually ends up selling through private listings with no meaningful premium and takes longer to sell?

Private listings, pocket listings, whisper listings, etc., serve a niche need in a housing market and do have their place. But the scale of the Compass private listing effort will be unlike anything the U.S. housing market has ever seen. In what is likely the largest purchase of their lives, I fear for the buyers of U.S. real estate — half of every transaction — to whom information is hidden by design in private listings on the claim that it is the seller’s right to determine the terms of selling their asset by withholding legitimate information from buyers needed for price discovery. Weird and concerning when you really think about it. What am I missing?

Final thoughts

More than half of listings in 2025 required price cuts, as sellers clung to aspirational asking prices, damaging their outcomes in the process. Overpricing lengthens days on market, forces multiple incremental price reductions and potentially leaves a reputational “scar” that persists even after the asking price is brought back to reality. Regional and brokerage data show that markets with tighter inventory, such as the those of the Northeast and Midwest, have lower delisting rates, while “testing the market” through private or pocket listings rarely results in quiet wins, since the vast majority of these properties end up going public with no clear, consistent pricing premium once FSBOs are removed (if it is even legitimate to cherry pick what market data is used in a market study).

This column originally appeared in HousingNotes by Jonathan Miller and is reprinted with permission. Miller is an adjunct professor of market analysis at Columbia University, director of markets at StreetMatrix and president and CEO of property appraisal firm Miller Samuel.